There are a large and growing number of archaeological discoveries that confirm key parts of the Biblical text. The page below should not be considered an exhaustive list of these artifact but hopefully a list of some of the more interesting finds.

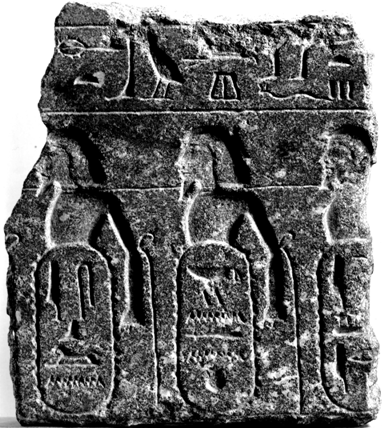

The Berlin Inscription

The Berlin Inscription might be the earliest reference to Israel in the archaeological record. The inscription is now housed in the Egyptian Museum in Berlin. According to the Museum’s records, the block, most likely part of a statue base, was acquired in 1913 by Ludwig Borchardt from an Egyptian merchant.

The inscription is comprised of three name rings superimposed on Western Asiatic prisoners, the rightmost of which is only partly preserved due to substantial damage, probably incurred when the block was removed from its original context. Above the heads of the prisoners is a partial band of hieroglyphs which reads ‘…one who is falling on his feet…’

The first two names are easily read—Ashkelon and Canaan. Two German scholars point out that the names Ashkelon and Canaan largely were written consonantally and thus are closer to Eighteenth Dynasty examples from the reigns of Thutmose III and Amenhotep II, than to those from the times of Ramesses II and Merenptah.

The third name in the inscription presents difficulties because the right side of the inscription is broken off. A detailed examination of the relief, however, allowed scholars to reconstruct the name as Y3-šr-il (‘Ishrael’), a name very close to Biblical ysr’l (‘Israel’). Egyptian scribes were not consistent in their usage of the hieroglyphs for ‘sh’ and ‘s’, and quite often interchanged them.

Read more at the Armstrong Institute of Biblical Archaeology.

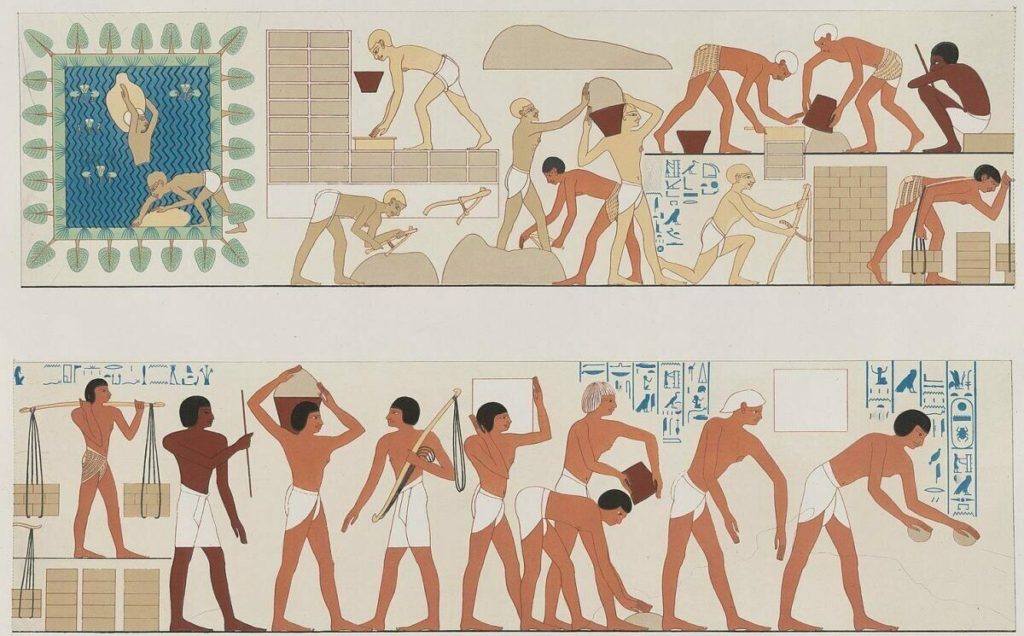

The Tomb of Rekhmire

Another interesting archaeological find is the tomb of Rekhmire, the vizier of Pharaoh Thutmose III, the pharaoh who Moses probably ran away from. Rekhmire is noted for constructing a lavishly decorated tomb for himself containing lively, well preserved scenes of daily life during the Egyptian New Kingdom. Interestingly, one of those scenes includes images of slaves making bricks.

The Soleb Inscription

At the end of the 15th century B.C., the Egyptian Pharaoh Amenhotep III built a temple to honor the god Amun-Ra at Soleb in Nubia (modern-day northern Sudan). Within the temple area are a series of columns on which Amenhotep III listed the territories he claimed to have conquered. Each territory is listed by a relief of a prisoner with their hands tied behind their backs over an oval “name ring” identifying the land of the particular foe. The most interesting from a biblical perspective is a column drum that lists enemies from the “the land of the Shasu (nomads) of Y·H·W·H” (the Tetragrammaton).

Given the other name rings nearby, the context would place this land in the Canaanite region. In addition, the prisoner is clearly portrayed as Semitic, rather than African-looking, as other prisoners in the list are portrayed. Two conclusions are almost universally accepted: this inscription clearly references HaShem in Egyptian hieroglyphics (the oldest such reference outside of the Bible), and that around 1400 B.C.E. Amenhotep III knew about the God of the Hebrews. Moreover, it would indicate an area in Canaan in the late 1400s B.C.E. inhabited by nomadic or semi-nomadic people who worship the God HaShem.

Read more at the Armstrong Institute of Biblical Archaeology.

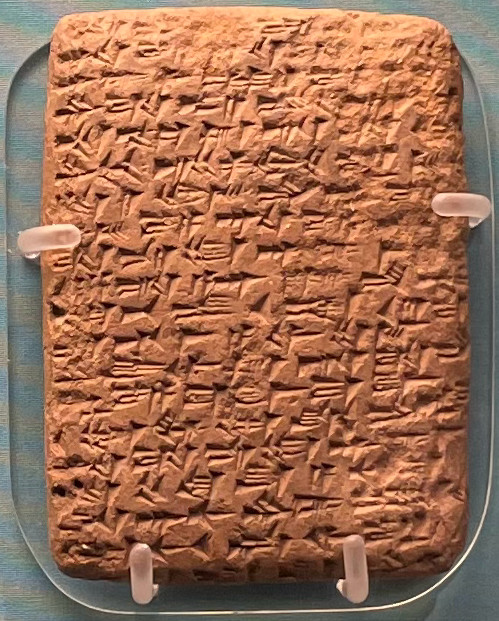

The Amarna Letters

The Amarna Letters are hundreds of clay tablets found in the royal archives in the Egyptian city of Amarna, dating from around the time of the conquest of Israel (1400-1350 BCE). These letters were sent to the Pharaoh by city leaders in Canaan, often to request assistance and complaining that a group called the Habiru or Hapiru are destroying cities and defeating the Canaanite armies.

The clay tablet pictured here (from a photo I took at the British Museum) is inscribed in Babylonian cuneiform. It is a letter from the ruler Yapahu of Gezer to the Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep III or Amenhotep IV (Akhenaten), including a request for help against marauders called Hapiru.

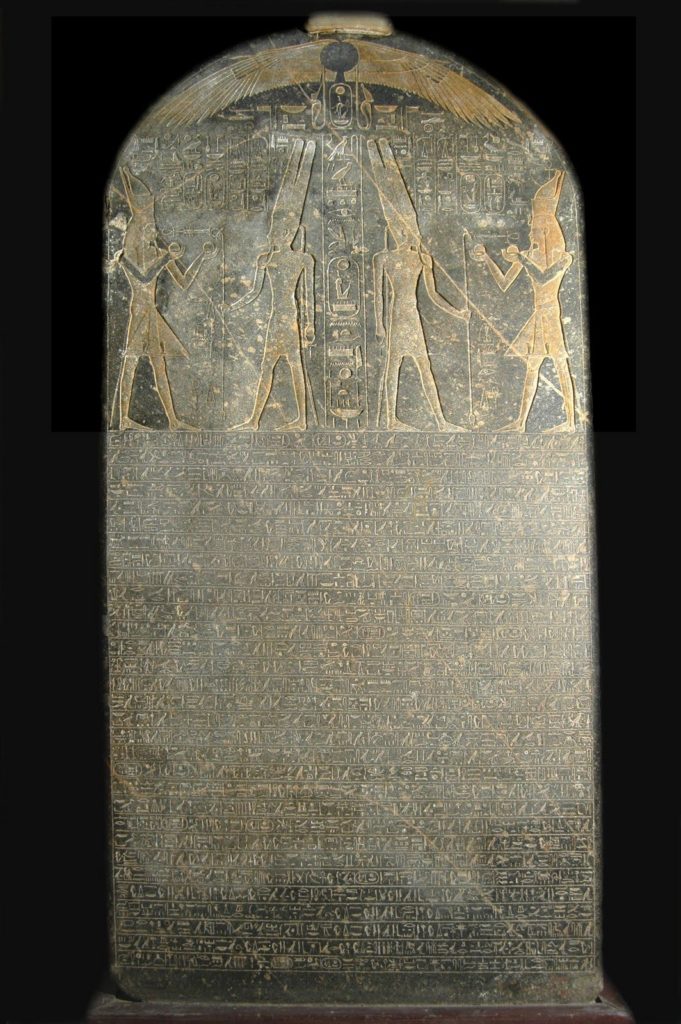

The Merneptah Stele

The Merneptah Stele is an engraved stone slab which describes Pharaoh Merneptah’s military victories in 1207 BCE. The stele mentions Ashkelon in a list of cities the pharaoh conquered. It also contains the earliest undisputed extra-biblical reference to Israel found to date.

Canaan has been plundered into every sort of woe,

Ashkelon has been overcome

Gezer has been captured

Yanoam is made nonexistent

Israel is laid waste, and his seed is not.

This reference shows that in the 13th century Israel was seen as a distinct people group in the land of Canaan. Given the dating of this artifact, an early date for the Exodus (1446 BCE) is more likely than a late date (1250 BCE).

Read more at the Armstrong Institute of Biblical Archaeology.

Proto-Aeolic Capitals

Proto-Aeolic capitals are large, intricately carved stones that served as toppers for columns and were common elements in First Temple period buildings—so common, in fact, that they are depicted on the modern 5-shekel coin. These capitals have been found in multiple locations around Israel, including one that was found at the base of the Stepped Stone Structure, the foundation of David’s palace. Archaeologist Eilat Mazar, who excavated David’s palace, postulated that that capital, discovered in a pile of debris from the time of the destruction of the First Temple by the Babylonians, may have originally been part of David’s palace. It has been described as the most impressive proto-Aeolic capital ever discovered in Israel.

The columns below were discovered in Megiddo, and can be seen in the ISAC Museum in Chicago.

Learn more at the Armstrong Institute of Biblical Archaeology.

The Mesha Stele

Most scholars believe that King Mesha of Moab created this stele, also known as the Moabite Stone, between 830 and 810 BCE and connect the events detailed in it to those of 2 Kings 3, which describes Mesha’s war against the kings of Israel, Judah, and Edom. The 3-foot-tall basalt stone holds 34 lines of Phoenician script, or paleo-Hebrew, recording the victories of King Mesha. It was originally set up in his capital, Dibon (modern Dhiban in Jordan). It says:

I am Mesha, the son of Kemoš-yatti [the god of the Moabites], the king of Moab, from Dibon… I made this high place for Kemoš […] because he has delivered me from all kings, and because he has made me look down on all my enemies.

Omri was the king of Israel, and he oppressed Moab for many days, for Kemoš was angry with his land.

And his son succeeded him, and he also said “I will oppress Moab!” In my days he did so, but I looked down on him and on his house, and Israel has gone to ruin, yes, it has gone to ruin for ever!

Omri had taken possession of the whole land of Medeba and he lived there in his days and half the days of his son, forty years, but Kemoš restored it in my days….

And the men of Gad lived in the land of Ataroth from ancient times, and the king of Israel built Ataroth for himself, and I fought against the city, and I captured, and I killed all the people from the city as a sacrifice for Kemoš and for Moab…

And Kemoš said to me: “Go, take Nebo from Israel!” And I went in the night, and I fought against it from the break of dawn until noon, and I took it, and I killed its whole population, seven thousand male citizens and aliens, female citizens and aliens, and servant girls; for I had put it to the ban of Aštar Kemoš. And from there, I took the vessels of Y·H·W·H, and I hauled them before the face of Kemoš.

[Then he includes a list of other cities he defeated…]

And Horonaim, the House of David lived in it. And Kemoš said to me: “Go down, fight against Horonaim!” I went down […] and Kemoš restored it in my days…

This stele contains some remarkable confirmations of the Biblical text.

- First, it confirms the family of Omri as the kings of Israel, including his son Ahab. Line 6 clearly implies that Mesha was already king of Moab at the death of Ahab (c. 853 B.C.E.).

- Second, it confirms the story of Mesha’s rebellion as seen in 2 Kings 3.

- Third, it includes the earliest absolute reference to the tetragrammation, the sacred name of God, in the Paleo-Hebrew script.

- Fourth, at the bottom of the stele, a second part of the text talks about the victories of Mesha in the South, with the conquest of the city of Horonaim against the “house of David”, that is, the kingdom of Judah. This reference was confirmed by archaeologists in 2022 after doing extensive research with the stele itself and an original papier-mâché cast taken of the stele before it was broken into pieces. Read about the House of David text here.

Learn more about the Mesha Stele at the Armstrong Institute of Biblical Archaeology.

Basalt Statue of Shalmaneser III

2 Kings 8:7–15 tells how a man named Hazael became king of Aram, a kingdom based in Damascus in modern day Syria. Elisha, following the instructions given to him by Elijah, anointed Hazael king. The current king, Ben-Hadad II was sick.

“But on the following day, he took the cover and dipped it in water, and spread it over his face, so that he died. And Hazael became king in his place.”

This usurpation of the throne is also attested to in a basalt statue of Assyrian king Shalmaneser III, who reigned 858–824 BCE. Below the waist of the statue, inscribed on his attire, are Assyrian cuneiform memorializing Shalmaneser III’s military conquests and building construction. The statue says:

Hadad-ezer passed away. Hazael, son of a nobody [Assyrian: mār lā mammāna], took the throne. He mustered his numerous troops; [and] he moved against me to do war and battle. [I] fought with him. I decisively defeated him. I took away from him his walled camp. In order to save his life he ran away. I pursued [him] as far as Damascus, his royal city. [I] cut down his orchards.

“Son of a nobody” is a sly way of pointing out that Hazael, who became a powerful king and ruled Aram for many years, was an assurper.

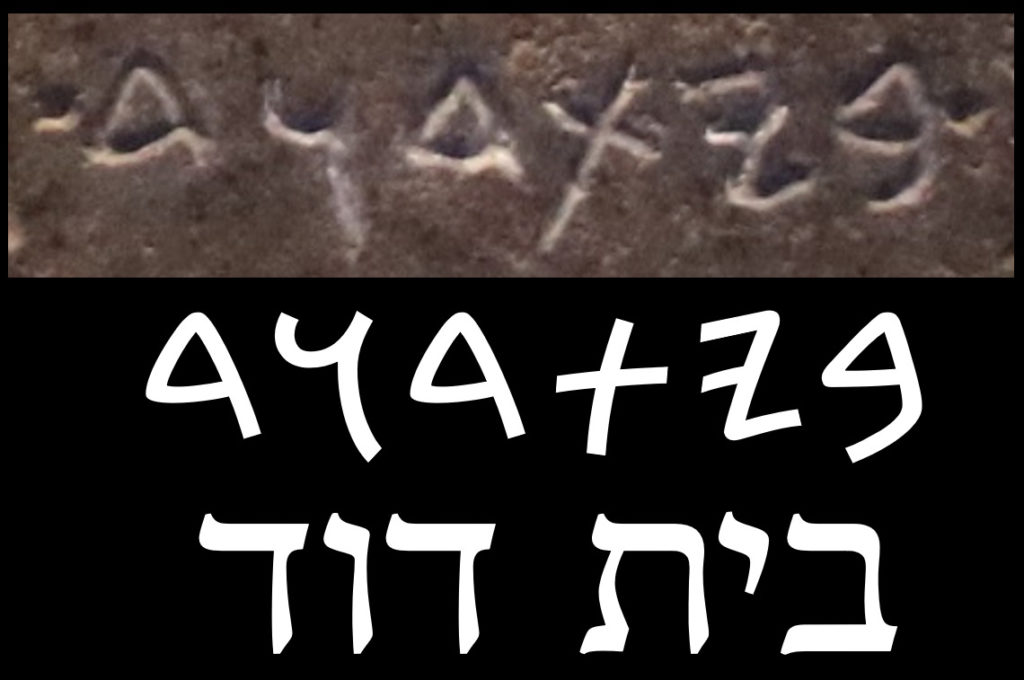

The Tel Dan Stele

The Tel Dan Inscription is one of the most important archaeological discoveries ever found. 2 Kings 9 tells the story of Jehoram king of Israel and Ahaziah king of Judah’s battle against Hazael king of Aram in Ramoth-gilead. Jehoram and Ahaziah left the battle so that Jehoram could travel to Jezreel and recover from an injury. Then one of the main commanders of Jehoram’s army, Jehu, was anointed as the new king of Israel and left the battle to stage a coup, killing both kings. From Hazael’s perspective, that whole incident was a victory, and a prime opportunity to create some propaganda.

Hazael wrote an inscription and placed it in the city of Dan, the northernmost city in Israel. It is a triumphal inscription, written in Aramaic, that corroborates the events that occur in 2 Kings 9. The text reads:

And I killed two [power]ful kin[gs], who harnessed two thou[sand cha]riots and two thousand horsemen. [I killed Jeho]ram son of [Ahab] king of Israel, and I killed [Ahaz]yahu son of [Joram kin]g of the house of David.

This is the earliest, most broadly accepted non-Biblical reference we have to King David and his family line. Before the Tel Dan Stele was found in 1993, most of the academic world was convinced that David never even existed. The only references to him were found in the Bible, and it seemed like the stories were more “King Arthur” than “George Washington.“ The text on the Tel Dan Inscription is undeniable, and even the most ardent anti-David experts have had to conclude that it is authentic.

As Rabbi Chaim Jachte says, “The discovery of the Tel Dan Stele had significance beyond proving the historicity of David HaMelech. It demonstrates the fallacy of drawing conclusions from the absence of archaeological evidence.”

Learn more at the Armstrong Institute of Biblical Archaeology.

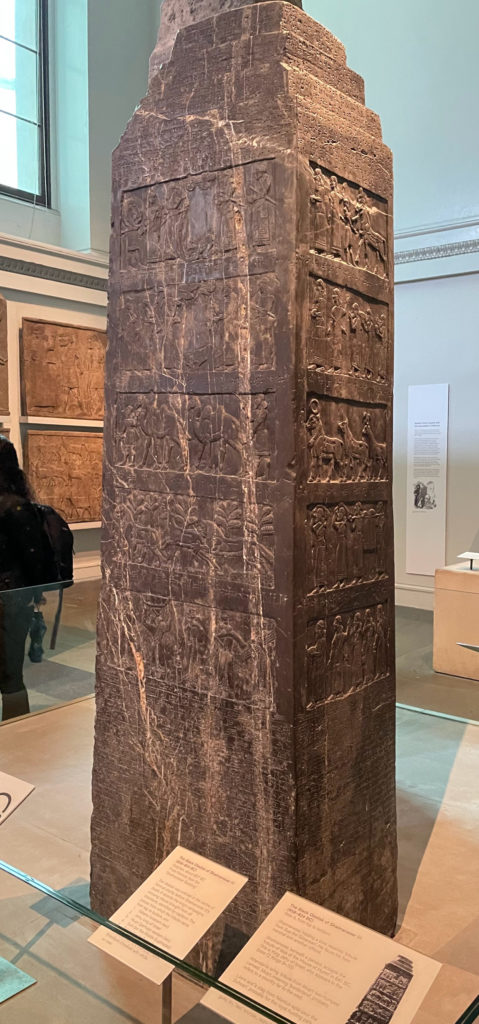

The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III

This victory pillar commemorates the deeds of Assyrian king Shalmaneser III, who reigned 858–824 BCE. It includes a panel on one side that depicts King Jehu bringing tribute to Shalmaneser III, and bowing down before him. The text above the scene says:

“I received the tribute of Jehu son of Omri (Akkadian: 𒅀𒌑𒀀 𒈥 𒄷𒌝𒊑𒄿): silver, gold, a golden bowl, a golden vase with pointed bottom, golden tumblers, golden buckets, tin, a staff for a king [and] spears.”

Jehu was not from the line of Omri, but given the power of Omri’s line, it’s not surprising that the Assyrians would connect him with that line. From their perspective, it’s really about which dynasty the land belongs to.

While we don’t have any version of this story in the Bible, the archaeology once again supports the Biblical characters.

The Chicago Prism

This hexagonal clay prism is one of two from Nineveh with the same royal inscription of Sennacherib (704-681 BCE) written in Akkadian using the cuneiform script. This prism, commonly known as the “Chicago Prism,” dates to 681 BCE. Written in the first person of the king, the text describes eight of Sennacherib’s military campaigns and the construction of a new palace.

In 701 BCE, Sennacherib laid siege to the city of Jerusalem, an event that is described both on the prism and in 2 Kings 18-19 and Isaiah 36-37. According to the prism, after being confined “inside the city of Jerusalem, his royal city, like a bird in a cage,” the Judean king Hezekiah submitted and delivered a great tribute to Nineveh. The Bible account also tells of a siege, Hezekiah’s submission, and the delivery of tribute, but it attributes Sennacherib’s retreat from the siege of Jerusalem to an attack from the angel of the Lord.